Sebastien Dabdoub

I’m watching Lauren trace the lines of polygonal shapes displayed on her phone, wondering what she’s about to tell me. Fireworks are blasting behind us, though we can’t see them from all the San Francisco fog, and I am sure that, at this moment, many beer pong games are happening across the country, set against the backdrop of red solo cups and crumpled Bud Light cans. Where I am though, on the night of July 4th, we are at Sebastien and Megan’s house, where there is an elaborate blue jello shot cake and a seven-layer dip and people are wearing animal costumes and Megan’s friend Lauren is deciphering the intersection of my and Sebastien’s birth charts on astro.com.

“Mhm,” she nods affirmatively, “okay, yeah, he’s a good match for you.”

Sebastien, sitting on the other side of the room, smiles at me and winks.

“In what way?” I ask.

“He’s a safe space for you,” Lauren replies. “He brings out the fun side in you, and you feel comfortable allowing him to do that.”

She is right. I think about the many moments over the last six years, from club nights and Pride parties to New Year’s Eve gatherings and movie outings, and Sebastien is always the common denominator across these memories. But one thing I don’t get. No one ever told Lauren when Sebastien was born.

“Wait,” I say, “how did you know his date of birth?”

“She read my birth chart when I started dating Megan,” Sebastien adds.

“Oh,” I light up realizing what that meant, “so Sebastien was vetted?”

“Yep,” Lauren replies.

Somehow, I can’t imagine Sebastien not passing the vetting test. He is the guy who gets along with everyone. Not because he is a people pleaser but because he always sees people for who they are, without any preconceived notions and without any hangups, and is genuinely interested in what they have to offer. In turn, even the people who don’t share any of his interests end up embracing him as part of their group.

Naturally, I thought he would make a great profile for the first issue of the magazine, so I asked Seb—which is how most of us call him—if he’d be willing to do the interview. Though initially hesitant, because he somehow had the absurd conviction his life was boring, he agreed.

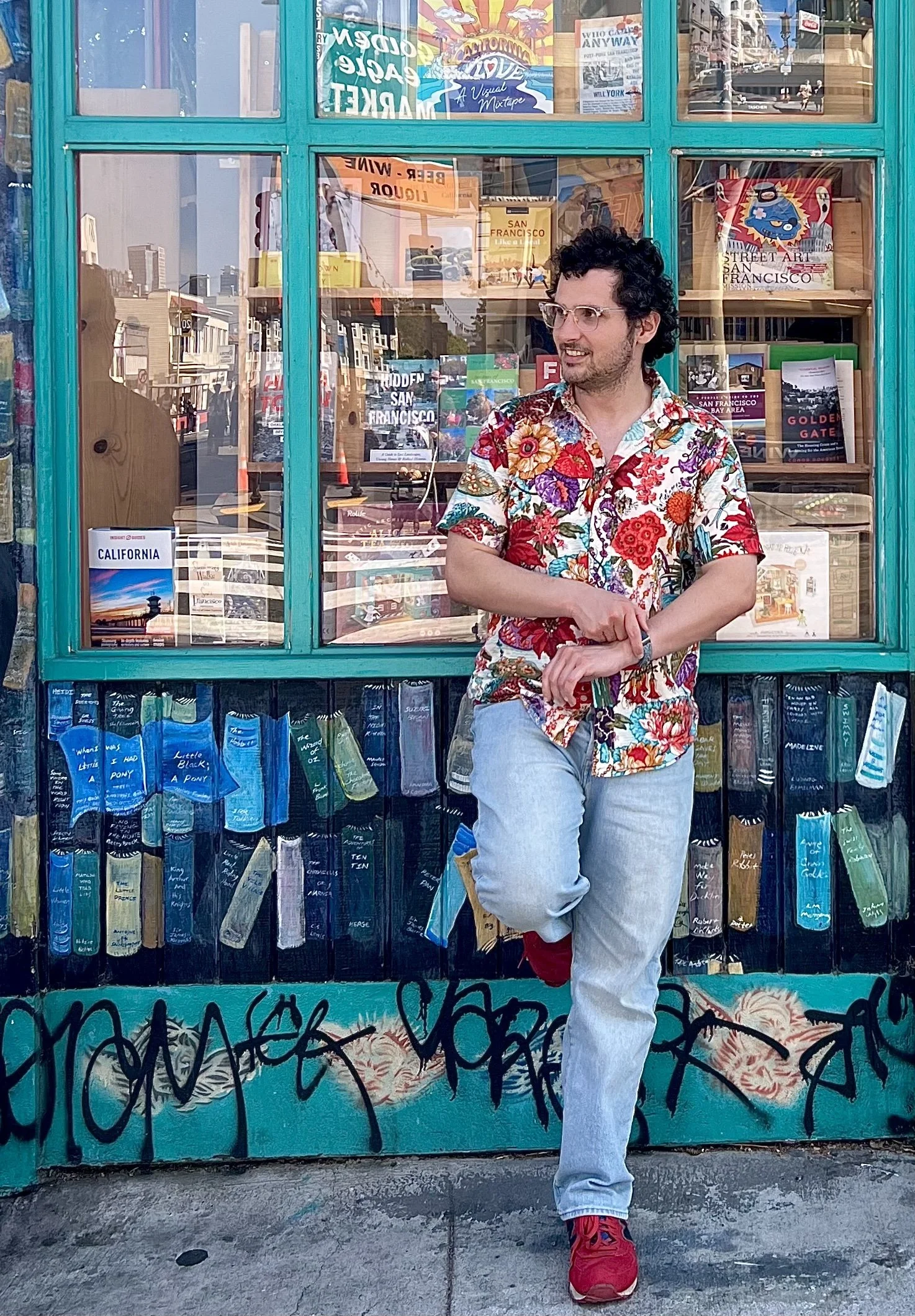

One month later, I meet him in The Mission at Media Noche, where I find him sitting outside, wearing relaxed light blue jeans, red New Balance sneakers, and a print short-sleeve shirt featuring a colorful bloom, from water lilies to flamingo flowers and bluebells.

Exactly four years ago, Seb and I were here with a few other friends, eating the greasy, protein-packed El Cubano sandwiches after the Polyglamorous’ Pink Block day party at The Great Northern, where Andy Butler of Hercules & Love Affair was playing a DJ set. I am not sure whether he remembers this and whether it is one of the reasons he picked this place, but I find it symbolic that four summers later, we are once again here and are sharing an El Cubano and two empanadas. Though Seb doesn’t bring it up, I also know Media Noche is where he and Megan had their first date when they started seeing each other.

“So, there are two ways of making empanadas,” Seb tells me. “One way is to do them baked, which is the South American way, and the other way is to do them fried, which is the Caribbean way.”

We’re eating the fried ones, a coincidence that is in no way insignificant even though Seb makes it sound so. Seb’s Cuban grandfather met his Spanish grandmother in Cuba, where they had lived for some time before they moved to Puerto Rico during the Cuban Revolution. His mom was born in Puerto Rico and moved to the continental US for college, ending up in San Francisco, yet another coincidence that I gladly point out to Seb, who will soon celebrate eight years of living in SF.

“Yeah,” he smiles, “mom tells me that The Mission was a very dangerous place back in the day.”

His mom eventually moved to Houston where she would end up meeting his dad, who was born in Bolivia but who actually descends from a line of Palestinians, which explains the Arabic origin of Seb’s last name, Dabdoub.

“I don’t think I have a strong sense of ethnic or national identity,” he says when I ask him how he sees himself. “Certainly a sense of Hispanic heritage from my mom’s side, and I lived in Bolivia for three years as a kid, and have a bunch of cousins there because my dad is one of six. But the Arab heritage for me was definitely more diluted. And, I certainly had some sense of otherness growing up in Florida, but even in Florida, a large percentage of people, especially around Miami, are Hispanic.”

When he was a kid in Bolivia, his parents decided to separate and Seb moved with his mom to Florida. It was Florida where Seb grew up and went to school, and it is Florida that comes to mind when I think of my first encounter with Sebastien. I was a freshman in college, participating in what I had no idea was the rush process for Number Six, a co-ed fraternity, and was overwhelmed by the amount of new people I was meeting, who—I would later learn—were sussing out whether I was someone they wanted to have around.

I remember feeling at ease around this senior from Florida who talked to me with genuine curiosity, unaffected and unrushed, despite being a well-liked and sought-out person at the parties. When I got my official acceptance into the group, I saw his name in the center of the card I got, scribbled with a red ballpen: “Congratulations! -Sebastien.”

Of course, “this senior from Florida” was as much as I knew about Seb’s life in Florida back then. Today, I have a more nuanced understanding. Seb was a nerd, a big reader, and a kid who was into computer science even before high school. But being a nerd wasn’t something that was celebrated in the environment he grew up in.

What was his way in, I ask. He might have been a nerd, but Seb’s present day ability to succeed in the wide spectrum of American social paradigms, from shirtless bros chugging beers at house parties to wallflowers discussing literature over a low-key dinner, is too conspicuous for me to believe that he was a maladjusted recluse.

“I did sports,” he says with a wry smile, “because that’s what you do in Florida.”

He did football, lacrosse, and wrestling, and emphasizes that he was quite good at wrestling, which he doesn’t need to emphasize because I’ve experienced it first-hand five years ago, at a friend’s Christmas party, when he tackled me to the ground after he told me he used to do wrestling and my response to that was: “You? Wrestled?”

He remained true to his core though and ended up taking AP Computer Science as a high school freshman, which was only available to seniors. Once he exhausted the one year of high school computer science and could no longer beg his teachers to make exceptions, he recruited two friends into an independent study class so that he could continue doing programming. He did programming competitions as well, but it soon became clear that the hard part of programming competitions was not coding—it was math.

So, when he came to MIT, he knew he wanted to do both computer science and math. One of the most formative experiences was taking advanced complexity theory, which Seb describes as brutally hard but incredibly rewarding.

“I went to the first class with my friend Santiago, who is one of the best math people I know, and we entered the class and he went ‘Shit. This class is literally all American math olympiad people.’”

But a curious nerd he was and so he stuck with the class. While the class officially dealt with limits of computation in a very mathematical way, what it actually provided Seb with was a lifelong skill to abstract problems and to ask the right questions. The homework problems required a great deal of creativity because he often had to do the harder thing in math: instead of proving that something was possible, he had to prove that something was impossible.

“Before that class,” he says, “it never occurred to me to question the limits. The class taught me how to think about life.”

He was not only flourishing intellectually but socially as well. MIT exposed him to people from all over the world, and he soon started deconstructing the narratives that he was taught growing up in the US.

“For instance, it wasn’t until I started talking to people at Number Six that I realized the US teaches history as a sequence of wars. And that’s not the case with many other countries.”

He learned more about political issues, such as the conflict between Israel and Palestine, from his friends. And he started getting more in touch with his Arab identity by getting closer to friends from countries like Jordan and Lebanon. By the time I met Sebastien in his senior year, he was already the Sebastien I know today: worldly, informed, and well-spoken.

We didn’t become friends immediately, however. In 2013, when I was in my second year, he moved to New York for his first job and our life paths wouldn’t intersect for another four years. Once we reach this time in his life story, I say that it’s the perfect moment to get moving. We buy ourselves Cokes and head over to Dolores Park, the second stop on his itinerary for our day.

By now, Seb knows how to thrive in this park. He has the 30+ SPF sunscreen, he has the comfortable blanket, he has his favorite spots on the grass (he prefers to be on the side closer to the Mission Dolores High School), and I’ve even seen him bring a foldable chair a few times.

We find a spot facing a group of dudes wearing alien costumes, who are standing right next to four shirtless, jacked guys playing pickleball. My eyes are following the pickle ball as it ping pongs between them until another shirtless guy, who looks like something between Matt Czuchry and Chad Michael Murray, starts doing handstands in front of us.

“It’s one of my favorite places in SF,” Sebastien says. “It’s warm and it’s great for people-watching. Any time I was looking for an apartment in the city, my one question was: ‘What’s the closest to Dolores Park I can get?’”

It’s one of the things he’s grown to appreciate about San Francisco compared to his previous life in New York, where he lived for two years after finishing his Master’s degree. At first, he really did not like SF. He moved because he and his ex-girlfriend agreed to do it at the time, but he kept saying that he would eventually go back to New York. New York was a night city, it had the clubs and the bars, and it was easy to find events even if you didn’t know people. SF was different. It’s a day city, house parties are more of a thing, and, as Sebastien points out, you have to know people to get to know the city.

“But once you do,” he adds, “once you have an ‘in,’ you realize there’s a lot to do here.”

A group of people closer to the public park restrooms, wearing tiny flags on their hats, start running up the hill and our conversation pauses momentarily. The crowds in the park are confused by what’s happening until we all see the same group of people running back down the hill. Everyone around us is now cheering. It’s not clear to me who will win this impromptu race but then one of the guys cleverly gains advantage by rolling down the hill.

The guy with the cleverly-gained advantage wins and Sebastien gives an applause.

“I love seeing weird stuff in here.”

I reconnected with Seb in 2017 when I moved to San Francisco. We were part of the same post-college crew so we naturally started spending more time together. While he seemingly fit all the classic stereotypes of an SF techie—he worked at Google, he was a software engineer, he lived around The Mission—I quickly learned that Seb was different.

If you spend time around transplants in popular cities, like New York or San Francisco or LA, who have graduated from top-tier universities or have worked at one of the coveted tech or consulting or finance firms, I am fairly confident that you will notice how elitist these circles can get. Socializing and dating will often be based on seemingly noble values, such as ambition or smartness, that are actually just a disguise for something far vainer: prestige and social status.

Seb was never a part of this narrative. In the six years of living in the same city as him, I have witnessed how readily open he is to every experience that San Francisco has to offer. It was Seb who helped expand many of our friends’ social circles in this city. It was Seb who helped us experience moments in the city that we would not have otherwise been privy to.

“I am a novelty seeker,” he tells me. “I love finding people who are different from me. It has always been like that.”

I mention that his way of thinking is very different from that of other people, and that people often complain how monolithic San Francisco’s culture is, how you can only meet other tech people in the city.

“No,” he replies assuredly. “We all live in the same place, we hang around similar spots, I don’t see how you would not be able to meet other people. That was always a mystery to me. It’s probably the elitism you mention, but I don’t want to participate in it. It’s just not my vibe.”

Seb’s openness to new experiences is a quality that I have always admired. There is a reason why he always ends up making friends with strangers, why he finds himself in social circles that otherwise don’t intersect, why he possesses social mastery despite being a nerd at heart, and ultimately, why he couldn’t be an elitist snob even if he tried. Because his fundamental belief, I would argue, is that every person has a story to tell and that each story is equally valuable, no matter the framework within which it operates. It’s why he can go from talking about the math behind general relativity to wanting to hear what astrology has to say about his life choices. It’s why he can spend a day playing simulation video games alone, and then go see a live musical the next day with a bunch of theater majors.

It’s also a quality that frightened me early on in our friendship. Seb often makes the point that it took time for the two of us to become closer. I have typically skirted the question by agreeing with him nonchalantly and saying that I simply needed some time to grow up, but the real answer is that I was scared.

For a long time, I was afraid of seeing myself for who I was. I was afraid of allowing myself to be who I was always meant to be, and what that really meant was that I avoided any situation that was too new, too unpredictable, and too untested.

It was easier to play it safe and be on the defense, and being around Sebastien meant that there was always a distinct possibility of something too offensive happening for my taste: ending up at a stranger’s party where people might ask me questions about my dating life, getting stuck in an intimate conversation where people I don’t know might talk about their deepest wounds, or even a one-on-one conversation with him that might eventually run dry because I have exhausted all the safe, neutral topics to talk about. I am not lying when I tell him I needed some time, but what I needed time for was learning how to live a little bit like him: unafraid and uninhibited.

We’ve reached the moment at the park when it’s just slightly too hot, so we get moving again. We stop by Dog Eared Books on Valencia Street to talk about reading, Seb’s favorite pastime. It’s packed inside, but we find solace in the science fiction section. Seb is a voracious scifi reader.

“What makes good science fiction?” I ask. “I feel like the word ‘sci fi’ has such a woo-woo connotation these days.”

“I would say,” he answers, “good science fiction guides what actual science could be in the future.”

Seb’s example of that would be Isaac Asimov, who wrote the Foundation series, and who came up with the concept of psychohistory, a branch of science that employs the law of statistics on large groups of people to predict the future in broad strokes. Or Cixin Liu with Dark Forest, the second installment of the Remembrance of the Earth’s Past series, who came up with the interspecies game theory, a way to strategize interactions with alien species.

“A more recent one to read would be Kim Stanley Robinson,” he adds. “He wrote a book called The Ministry of the Future, which deals with the concept of extreme ecoterrorism as a way to deal with climate change.”

His three favorite books of all time, across all genres are: Don Quixote by Cervantes, The Society of Mind by Marvin Minsky, and the Culture series by Ian Banks. The first one because Seb likes to see Don Quixote’s story as supportive of idealism, the second one because it helped Seb change the way he thinks about thinking, and the third one because it perfectly encapsulates high-quality science fiction.

“Do you have a favorite author?”

“Oh man,” he replies. “I mean, I do wish Ian Banks was still alive. What I wouldn’t do for more Ian Banks books.”

Seb buys The Twilight World by Wener Herzog and Golden Age Locked Room Mysteries by Otto Penzler, and then we leave the bookstore. He wants to take me to Radio Habana, a bar on 22nd and Valencia, but when we get there, we realize that the bar hasn’t opened yet. Seb is telling me about the funky exterior decor and says that the bar is owned by a Cuban couple who have made this place a staple in The Mission community. He loves coming here. I point out that it’s cool he picked another place referencing his Cuban identity as part of the itinerary.

“Huh,” he says, “I didn’t do that on purpose actually.”

We instead find a spot at The Beehive. I want to ask Seb about his work because he is usually not one to bring it up on his own. Seb is now a software engineer at Netflix, working remotely from his place in The Mission, and specializes in distributed systems.

Another evidence that Seb doesn’t fall into the typical stereotypes of a San Francisco techie is that he never talks about his work in terms of some nebulous mission, which is what you’ll usually hear when you ask someone in tech why they do what they do. Instead, what he loves doing is building elegant solutions that address really complex problems. In that sense, he is a true engineer at heart.

Distributed systems can be best understood as the answer to the unfortunate reality that a single computer can have only so much processing speed, memory capacity, and reliability. So, when you have something like Netflix, which is tons of movies and tons of TV shows watched by tons of users all across the world, you have to use tons of servers to have Netflix operate smoothly.

That creates all sorts of interesting problems because you have to figure out how all this computing power should be split into smaller tasks so that every machine can perform in the most optimal way. That’s where Sebastien’s work comes in. And his work is direct evidence that not all interesting engineering problems happen in either academia or startups.

“Actually, the most interesting research in distributed systems happens in large corporations,” he says. “For distributed systems, you need to have scale. And, there is only so much scale you can get with a small tech company or in an academic research project. I definitely appreciate the academic side of things, but what’s interesting to me in my field happens at big companies.”

There was a brief period of time when younger Sebastien, a video game fan, thought he might want to work in the video game industry. But he quickly learned that someone like him would not enjoy working in that type of field. Why, I ask him.

“The usual stuff that you do when you’re building video games professionally, like the graphics and the story, is not what excites me. I get inspired by thinking about how you would write code for my favorite genre, simulation video games.”

Seb describes simulation games as having a set of constraints within a world that allow for random generation within those constraints. The Sims, for example, is character simulation. A more general example would be a character walking next to a river in a video game, and having multiple possible scenarios: either ignoring the river and doing nothing or digging a hole in the ground and now having the river flow through.

I think about the dug hole and the river that’s suddenly flowing through, and Seb’s openness to any possible scenario of social life in San Francisco, and his love of science fiction that posits new possibilities for future science, and the advanced complexity theory class that taught him to question the limits, and I realize that everything that Seb does is driven by a single motivation: to test the boundaries of what is possible.

It is getting late, and people are starting to trickle down to The Mission for a Saturday night out. Seb has been answering my questions for hours and I can tell that his introverted self is ready to bid adieu and not see me for at least a few weeks. I ask him what he’s planning to do that night, and he says he might chill with Megan at the house and have a low-key evening.

At 10:50 pm, about four hours later, I get a text from Megan saying, “What did you do to him?! He’s been asleep since 8:45pm. He mumbled ‘power nap’ and then left this earthly plane.”